By Peter R. Kann

April 25, 2025 4:32 pm ET

Editor’s note of WSJ: This article appeared in the Journal on May 2, 1975. Saigon fell to the Communist North on April 30.

Additional notes (April 30, 2025) were offered by members of the Class 30, Vietnamese National Military Academy, Republic of Vietnam. The article is a “gift unlocked” from WSJ by Le Nhu Tuan, H30.

South Vietnam, or rather the South Vietnam that I have known for seven years, has passed away.

There probably are a great many Americans who breathed a sigh of relief when they heard the end had come. There undoubtedly are some Americans who wished, for whatever reason, that South Vietnam had expired much sooner. But surely there also are some Americans who mourn the passing. I am one of them.

For me the collapse of South Vietnam was like the death of an old acquaintance. Much as I often criticized South Vietnam I don’t think it deserved to die.

South Vietnam’s faults and failings always were much more visible than its strengths and I, like most reporters, tended to focus at least my professional attention on what South Vietnam was doing wrong. Few societies, and certainly few small and frail ones, ever have been subjected to the degree of sustained critical attention that Vietnam was. I and a thousand other reporters dissected its every aspect, analyzed its every mistake, exposed its every flaw (1). This is not to say South Vietnam would have fared better or survived longer had the spotlights been turned off (2), but conceivably there might be a few more sympathizers at the funeral.

In the end, of course, the severest critics and profoundest pessimists proved to be right. South Vietnam may have survived longer than some pessimists expected, but it did collapse—suddenly, chaotically, completely. And, I think, tragically (3).

South Vietnam was, to my mind, no better but no worse than a great many other societies around the world. In at least some ways it was not so very different from our own. Obviously South Vietnam’s social structure, government and army ultimately were too weak to resist the Vietnamese Communists. Less obvious is the thought that South Vietnam did manage to resist for a great many years and not always with a great deal of American help. Few nations or societies that I can think of would have struggled so long.

It is true that South Vietnam lacked a unifying and motivating cause that could compete with the Communist crusade. Anti-communism never was compelling or even comprehensible to most South Vietnamese (4). Capitalism, as represented by Honda motorbikes and other imported goodies, was not a cause that captured hearts and minds. Nationalism was a contested cause and if only because the American presence had been so great in South Vietnam the Communists seemed to be the true nationalists. So South Vietnam was a country without a cause. But now stop to consider: What cause would motivate you or me to fight for 25 years?

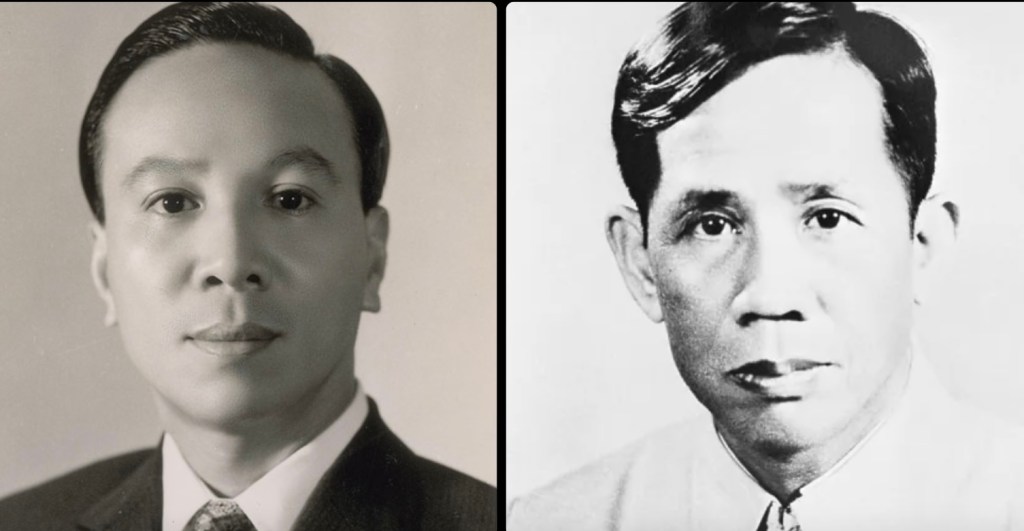

It is true that South Vietnam lacked the kind of creative, dynamic leadership that conceivably might have coaxed more spirit and sacrifice from a war-weary nation. President Nguyen van Thieu was no charismatic statesman. He was an introverted and suspicious military man who proved surprisingly adept at playing palace politics but who never truly learned to lead. But was Mr. Thieu really any less of a leader than scores of other retired generals who rule semi-developed nations around the world? I think not. He was, by his own lights, a Vietnamese patriot (5). And, before being too hard on failed South Vietnamese leaders, perhaps one ought to stop to list the names of truly popular and successful statesmen anywhere in the non-Communist world today. My own list could be written on a Bandaid. It is true that South Vietnam’s politicians and people never seemed to be able to unite, that the society seemed divisive and sounded discordant. Saigon’s chaotic traffic frequently was cited as symbolizing the society’s lack of order and discipline. But what non-Communist society these days can claim any great degree of political unity and social cohesion? Do we, by our values, venerate order and discipline as social goals or moral virtues? Are the best societies really those in which the trains all run on time and the people all march in step?

It is true that South Vietnam never was really democratic. Its democratic institutions, imported from America along with bombs and bulgur wheat, were more show than substance (6). And yet, if only because the South Vietnamese government never was very efficient, South Vietnam, unlike North Vietnam, never qualified as a totalitarian state. There were political prisoners and torture chambers and other elements of sometimes harsh authoritarianism (7). But there also were some limitations on the power of the president, there was fairly widespread—and not always whispered—criticism of government policies, there was a surprising diversity of individual opinion and behavior (8). Might South Vietnam have fared better had it been more authoritarian, more rigid and ruthless? I doubt it (9). But I also doubt that it would have fared better had the legislature exercised more power or had press controls been relaxed.

It is true that South Vietnam was corrupt. The corruption was more widespread and more serious than simply a few fat generals salting away millions in Swiss bank accounts (10). The whole system was in some sense corrupt. At the lowest level it was a simple matter of government clerks supplementing meager incomes with petty bribes. At a higher level it all too often was a case of jobs being sold to men who could pay rather than given to men who could perform. At the highest levels there were some cases of outright venality (11). But not all, perhaps not even most, South Vietnamese officers or administrators were corrupt. It is not excusing Vietnamese corruption to point out that it exists to roughly the same degree in almost every Southeast Asian country. Nor is it excusing Asian corruption to note that few Western societies are so pure that they can cast many stones.

It is true that South Vietnamese society was inegalitarian and elitist. Its rich were too rich and its poor too poor and the disparities were all too visible (12). Money and position bought privileges like draft deferments and, at the end, escape (13). Yet the disparities in Vietnam actually were less glaring than those in a score of other American-allied states from the Philippines to Brazil. The South Vietnamese peasant, when the war was not being fought in his particular paddy, was a prosperous small farmer by Asian standards. I am not minimizing the misery of the millions who passed through refugee camps when I note that there also were some millions of small farmers who owned their own land and made a fair living from their crops. The South Vietnamese peasant, in short, was not a downtrodden serf waiting for liberation from some slave master.

It also should be said, or confessed if you will, that there were many likeable people among the elite who ruled Vietnam. Almost every reporter who spent any time in the country befriended some government official, army officer, business man, politician—some member of that elite. These people frequently were all too remote from their own countrymen and countryside. Many were too wealthy or too Western-oriented to have much rapport with peasants or soldiers (14). They were not the best sort of people according to some biblical, or Buddhist, value scale. But some of them were my friends and I will miss them.

It is true that the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) in the end proved to be no match for the North Vietnamese army. The end was an inglorious six weeks of retreats, routs, chaos and collapse (15). Still, the AVRN was not an army of bumblers and cowards. It was an army that stood and fought well at a score of places whose names we have all forgotten. And it stood and fought well in a thousand little engagements and in a thousand little mudwalled outposts whose names no American ever knew.

It was an army of soldiers who deserved better leadership than they got (16). It was an army that for years watched the Americans try to combat the Communists with every wonder of modern weaponry and which then, all too suddenly, was left to face the Communists with American-style tactics but without American-style resources. It was a Vietnamese army that perhaps never should have been Americanized and thus never would have required Vietnamization. It was an army that for years was ordered to defend every inch of Vietnamese territory and which tried, with greater or lesser success, to do just that. When suddenly it was told to abandon cities and provinces it effectively abandoned the war (17).

It was not an army of officers and men who tended to charge impregnable enemy positions, or who would have been willing to live for years in holes in the ground with B-52 bombers pounding the earth around them, or who would have made the long and terrible trek down the Ho Chi Minh Trail, or who went into battle motivated by the thought that their almost certain deaths would serve some more noble goal. The North Vietnamese army is that kind of army, but how many others, including our own, are fashioned in that mold? The South Vietnamese army was an army of simple soldiers who, without a cause, fought on for more than two decades. Several hundred thousand of these soldiers died. More than half a million were wounded. And, in the final weeks of the war, when every American in Saigon knew the war was lost, some of these soldiers continued to fight at places like Xuan Lac and thereby bought a bit of time for the Americans and their chosen Vietnamese to escape with their lives. It was a much better army than it appeared to be at the end.

It is true that South Vietnam got a great deal of help from America and became too reliant upon us. Soviet and Chinese troops never fought in Vietnam as American troops did (18). For much of a decade South Vietnam was, for most practical purposes, an American colony (19). The U.S. army took over the war and for a time promised to win it. The U.S. taxpayer financed Vietnam. Washington set Saigon’s policies and the U.S. Embassy in Saigon largely fashioned Vietnam’s politics. South Vietnam was not always a docile puppet and at times it failed to dance to American tunes. But over the years South Vietnam came to assume, indeed was led to assume, that America was its patron and protector. It was not an unreasonable assumption. Nor then was it entirely unreasonable for Vietnamese to sometimes shrug off responsibility for their own failings, to blame the U.S. for their problems, and, toward the end, when America lost heart for the war and lost interest in Vietnam, to be bitter at America and Americans (20).

In the end the stronger side won. The Vietnamese Communists had more strength and more stamina. They had a cause, a combination of communism and nationalism, and they pursued that cause with almost messianic motivation. They persisted against all obstacles and at times against all odds and they finally succeeded (21).

But the stronger side is not necessarily the better side. “Better” becomes a question of values and much as I may respect Communist strength and stamina I cannot accept that the Spartan Communist society of North Vietnam is better than the very imperfect South Vietnamese society that I knew (22).

This is an obituary for that South Vietnam. It cannot be an obituary for the country of Vietnam or even the people of Vietnam. Countries don’t die. South Vietnam will continue to exist for some months or perhaps a few years with a new government, new policies, a new social system (23). Then it presumably will merge with North Vietnam and this enlarged Vietnam will dominate Indochina and will become a major force in Asia as a whole. It will be a nation of 40 million hardy and hardened people. It will be rich in natural resources. It will have one of the finest, maybe the finest, army in the world (24).

Perhaps the energies of 40 million Vietnamese will be devoted to further political and military expansion. In either case Vietnam will merit, and probably command, world attention in years ahead. Some South Vietnamese enthusiastically will embrace a new system and new society. Some will have trouble adjusting but eventually will find a place in the new order. Some will be unable to accept the new order, or will be unacceptable to it (25). They will be discarded in one manner or another, but their children will be brought up to be part of the new society (26).

The new Vietnam will be powerful and successful (27) and those are the qualities that seem to count among nations, as among men. History books tend to deal with the same themes and history thus is unlikely to look kindly on the South Vietnam that failed to survive. But this is not history. It’s just an obituary for the South Vietnam that I know.

Mr. Kann is a former publisher of the Journal and CEO of Dow Jones & Co. He was a Journal staff reporter who had covered the Vietnam war when he wrote this article.

Notes by Class 30 – Vietnamese National Military Academy

1) Biased anti-war writings, television shows from legions of US reporters misled the American voters and Congress. As a result, the US aid to South Vietnam for the 1974-1975 fiscal year was reduced to $700 millions – adjusting for aid transportation, inflation, and other expenses, it was just about 1/3 of the amount SVN received in 1973, after the Paris Peace Agreement. The US military force would be paralyzed if it lost 2/3 of its budget. ARVN was simply out of ammunition at the start of 1975. This was the main reason why the Republic of Vietnam collapsed.

2) If it received the 1.41 billion dollars in aid as promised after the Paris Agreement, the Republic of Vietnam would not only survive, but would also grow substantially in multiple aspects, and become strong enough to venture out to the North and liberate it.

3) The VNCH 1974-1975 fiscal year ran from July 1974 to June 1975. By intensity of usage level, the ARVN ran out of ammunition, fuel, spare parts by January 1975. It was tragic as the ARVN soldiers had to fight against the North Vietnamese tanks and 130mm field guns supplied by Soviet Union with hands, teeth, and daggers.

4) South Vietnames were terrorized by VC, and consequently very fearful of them, esp. after the Tet Offensive in 1968. When ARVN soldiers withdraw from a village, villagers simply abandoned their own. They constantly lived in fear, when night fell, the VC guerrillas came knocking on the door to arrest or kill. According to Douglas Pike, an estimated 465,000 people in the South died and 935,000 were injured. Only about a thousand people in the North died or injured from the bombings.

5) President Nguyen Van Thieu had no citizenship other than of the Republic of Vietnam (VNCH), while Le Duan proudly stated of having two fatherlands – Vietnam and the Soviet Union during the 23rd Plenum of the Soviet Communist Party.

The North Vietnamese leadership prioritized communism over the welfare of Vietnamese. When The Paracel Islands were attacked by China, they feebly reacted in words. Their focus was to please their bosses – China and Soviet Union, to receive guns and ammunition. The children of the North Vietnamese Politburo members were completely absent from the battlefield in the South.

6) South Vietnam was not developed enough to enjoy democratic principles and its fruits. The imposition of American democratic principles on the Republic of Vietnam was a patronizing and foolish act by American politicians. The people of the South Vietnam were simply concerned with their own security, food, clothing, Honda scooters, and education for their children.

7) Thousands of prying reporters, representatives of the Red Cross and religious organizations from the US looked after the VC prisoners, who were somehow more fortunate than the regular ARVN soldiers.

The VC prisoners went on hunger strikes and sang communist songs all day in Côn Sơn, Phú Quốc island, and no one dared to say a word. In 1973, the ARVN returned more than 43,000 plump prisoners to North Vietnam (more than 4 divisions); among them, at least one became a general to lead the charge against the South in 1975.

According to the confessions of captured North Vietnamese soldiers, the prison time in the Côn Sơn, Phú Quốc Island were the happiest time of their lives; and they tasted chocolate many times.

8) South Vietnamese could openly criticize Nguyễn Văn Thiệu and Nguyễn Cao Kỳ, but under the communist regime, before and after 1975, anyone criticized government officials, big or small, they would be imprisoned, possibly for life or even executed. Officials of the VNCH government were very afraid of reporters, even domestic reporters, a frivolous accusation could cost them their jobs.

9) South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore all had strict, authoritarian governments compared to the Republic of Vietnam, and all were very successful. The Republic of Vietnam government during the Second Republic under President Nguyễn Văn Thiệu was ineffectual and somewhat demagogic, even during the war. They were very afraid of the press – domestic or international. If the regime of President Ngô Đình Diệm had not been overthrown, South Vietnam would have developed into a strong economy, no less than South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore.

Besides, it was shameful when the US government, in the name of democratic principles, assassinated Ngô Đình Diệm, the president of an allied country, just because of disagreements on policy. So, let’s say Zelensky, the president of Ukraine, was assassinated by the US government because of disagreements on policy…

10) Former ARVN generals in America had very hard lives. The corpulent general mentioned in this article may be the notorious General Dang Van Quang. But, all of this was just false and slanderous. The Republic of Vietnam and its people was brought down by million articles from legions of dishonest American reporters and others. The hardships and injustice of General Dang Van Quang were written by author R.V. Schheide in the article “The Trial of General Dang” in the Sacramento News & Reviews on December 4, 2008, and will be reposted on this K30 website.

11) It could be a reference to President Nguyen Van Thieu. However, it is just a typical slander in vogue during the Vietnam war from American journalists or VC sympathizers. President Thieu lived simple for nearly 10 years until death in the city of Foxborough, Mass, a middle-class area. Stories of oligarchs dining on gold-plated beefs are only for current members of the Politburo of the Vietnamese Communist Party – a topic conveniently ignored by American journalists.

12) The poorest people are not farmers, but ARVN soldiers and small officials of the Republic of Vietnam. They bore all all sufferings of the war, and have been persecuted after the war, until now – 2025, even though it has been 50 years. – two generations. The most miserable people on the streets of Saigon are their children and grandchildren.

13) None of the children of the Politburo members of the Communist Party in the North were present on the battlefields in the South during the Vietnam war. Their children were often sent to study or work in Russia and Eastern European countries during the war.

14) The lucky ones were about 130,000 South Vietnamese who were evacuated just in time before the fall of Saigon. But none thought they were rich, just a little luckier. Most people constantly lived in fear in the South during war, not knowing what tomorrow would bring.

15) ARVN soldiers retreated in disarray when they realized their guns were out of ammunition, their vehicles out of gas, their planes no spare parts to fly, and their military aid had all been used up. “We have been betrayed.”

16) According to a North Vietnam high rank officer, Bui Tin – the mid-level officers of the ARVN– battalion and regimental level – were capable, professional, and courageous; while the senior commanders were half-baked and corrupt. Le Duan himself believed that the major offensive after the 1973 Paris Peace Accord had to start quickly before the South Vietnamese army matured and was commanded by younger-generation officers.

17) This was a fatal, panic-stricken decision by President Nguyen Van Thieu and his commanding officers, that sealed the fate of South Vietnam. The South could have been saved and recovered, even after the fall of Ban Me Thuot.

18) Recently, North Vietnam itself admitted that there were Russian and Chinese soldiers in North Vietnam supporting the war effort.

19) If they knew how to take advantage, the Republic of Vietnam would thrive by providing services to more than 500,000 American soldiers, a form of domestic export.

South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore rose thanks to the Vietnam War. After fighting in Vietnam, returning South Korean soldiers often saved enough money to buy a house, or send their children to college, or get beautiful bribes; their children were very successful later on.

20) The 2/3 cut in US aid, along with the lack of adroitness of the South Vietnamese leaderships, led to the collapse of the Republic of Vietnam in the face of the North’s offensive in 1975. The Republic of Vietnam could still have withstood if it had a determined and flexible government despite the aid cuts. If the promised aid had continued, an average leadership could have repelled the offensive.

21) The communist society in the North Vietnam forced young men to go to the South to fight so that their parents and families could have food to eat in their villages, very similar to the life in North Korea that they often praised through many songs sang during the Vietnam war (… brave North Korea). However, the fate of the Republic of Vietnam was decided by the Watergate, and leftish fake news, deceitful press system of US.

22) The bright spots and highlights of Southern society during the 20 years under the Republic of Vietnam can be seen through literary works, poetry, musicals, films, fashion (ao dai dress), architecture, … The only cultural product of the North after 70 years (from 1945 – 2015) is the pith hat. According to this article, Southern farmers lived well compared to farmers in Southeast Asian countries, and the majority of South Vietnamese people were farmers.

23) Within two years after April 30, 1975, the National Liberation Front figures were almost eliminated and a few were lucky enough to flee the country, such as Truong Nhu Tang, Minister of Justice of Provisional Revolutionary Government of the Republic of South Vietnam (VC)

24) The ten years after the April 30, 1975 event were the most miserable times in the history of the nation, as confessed by the Vietnamese communist party members themselves. There was no rice to eat, even for toddlers, children. Their patron, the Soviet Union was exhausted and about to collapse. The Vietnamese communist army was probably the largest in terms of population, and had the most knives and machetes – could not produce a single bullet. The Vietnamese communists begged to become a vassal of China to survive with the secret treaty of Chengdu.

25) After April 30, 1975, South Vietnam became a large prison camp, and about 1.2 million people were locked up in labor camps, some for up to 18 years. Outside, the communist government completed three consecutive offensives called “attacking the bourgeoisie, capitalists”, robbing the homes and properties of the people in the South Vietnam, throwing them into the so-called new economic zones, and then paying tribute to Russia with 40 tons of gold. Not limit to the shore, more than three hundred thousand Vietnamese boat people perished in the open sea escaping communists. This was the greatest victory of the Vietnamese Communist Party in Vietnam and also a crime against humanity.

26) Most of the poor and miserable people on the streets of Saigon in 2025 are the grand children of ARVN soldiers. Even after 50 years, they are still tortured and despised – children, grandchildren, like slaves. Every time they apply to school or work, they are still asked about their ARVN grandfathers’ background, even though they have been dead for quite a long time.

27) In 2016, the Trump administration sought to isolate China economically, encouraging Southeast Asian countries such as South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, and Japan to invest in Vietnam, helping Vietnam reduce its dependence on China. American companies in China were also encouraged to move to Vietnam. Even Chinese companies moved to Vietnam to avoid US tax policies. Thanks to the investment and cash influx from many countries at the request of the US, Vietnam’s economy began to lift off after 40 years of stagnation, backwardness, sufferings.

FOMO, in 2025, Trump organization had the groundbreaking for 1.5 billion luxury golf project in Hung Yen, Vietnam.

However, to do the justice, companies from US, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore should set a quota to hire the outcasts, the true victims of the Vietnam war.

You must be logged in to post a comment.